Somehow the engine was rebuilt twice, within a fortnight.

In my adventures of fixing, rebuilding and playing with old sports cars, I met a friend, Danny, who was in the need of seriously saving his Subaru Impreza WRX.

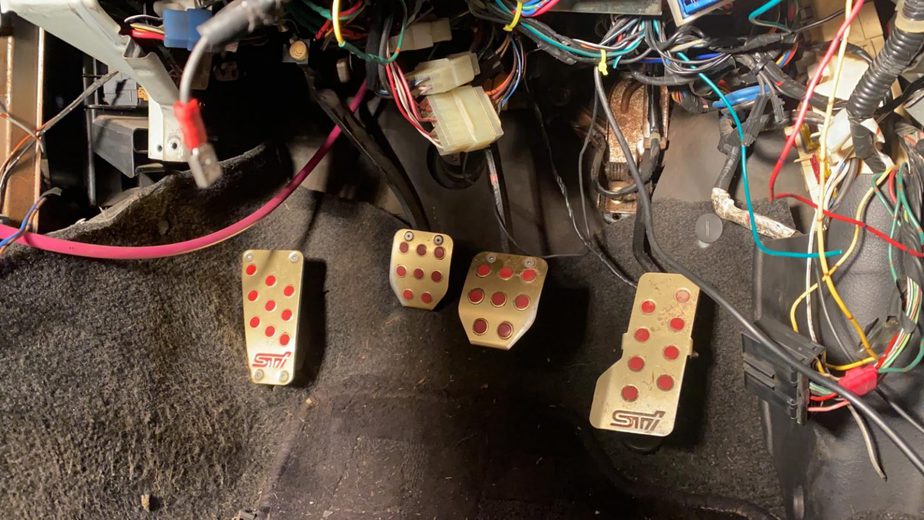

He’d been sold a less than perfect, but mostly solid JDM import WRX from a private seller. By less than perfect, I mean it was in dire need of attention. The engine wasn’t running correctly, half of the dash lights didn’t work, the wiring looked like it had been attacked by someone you’d see on an episode of Cowboy Builders and the battery had leaked, which made a nice mess of the chassis frame rail.

Him and his dad George took the brave job of stripping the car down and removing everything from the engine bay at a local workshop; where I met them and asked about their car. Realising they had no experience taking apart a car – let alone a 90s turbo car with a plumbing monstrosity – I offered my help to rebuild the car.

George and Danny tackled the corroding frame rail rather eloquently. George is a retired engineer; and had no problem fabricating new steel plates to cut the affected frame rail, reinforce it and re-plate it, resulting in a repair that you can only tell happened because of the fresh paint. He’s an old school metalworker; think of a plate and it’ll be shaped to a perfect fit and welded in very neatly, then ground down to be entirely invisible.

George had also enlisted the help of his brother John, to sandblast some of the brackets from the engine bay, and cover them in some epoxy primer and some underseal. It made a significant difference fitting brackets back to a car that weren’t covered in 15 layers of rust and salt.

Having never heard the car running myself, I had to rely off Danny’s description of the problems. From phrases like “it doesn’t idle properly” and “it hits a brick wall at about 4500rpm” – there were a multitude of problems that were impossible to pinpoint to a single cause without seeing the engine physically running. However, I suggested a full overhaul of the engine would be a good place to start, seeing as the car supposedly sat for 7 years while the mileage increased, according to the previous owner.

With the engine on a stand, I started by pulling the spark plugs. They were completely black and smelled very oily; which to me suggested the car was probably burning oil and was also probably running quite rich. My gut instinct then told me to just completely disassemble the engine as I noticed a few things that didn’t seem right. The EJ20 block didn’t seem to be the original block from the car, looking at the service manual and a few descriptions of some online forum posts. Clearly in my mind, someone’s pushed the original engine too hard in this car, and probably cracked it or caused some sort of significant bottom end damage, and just replaced the bottom end with a donor EJ20 from another car – perhaps a Legacy.

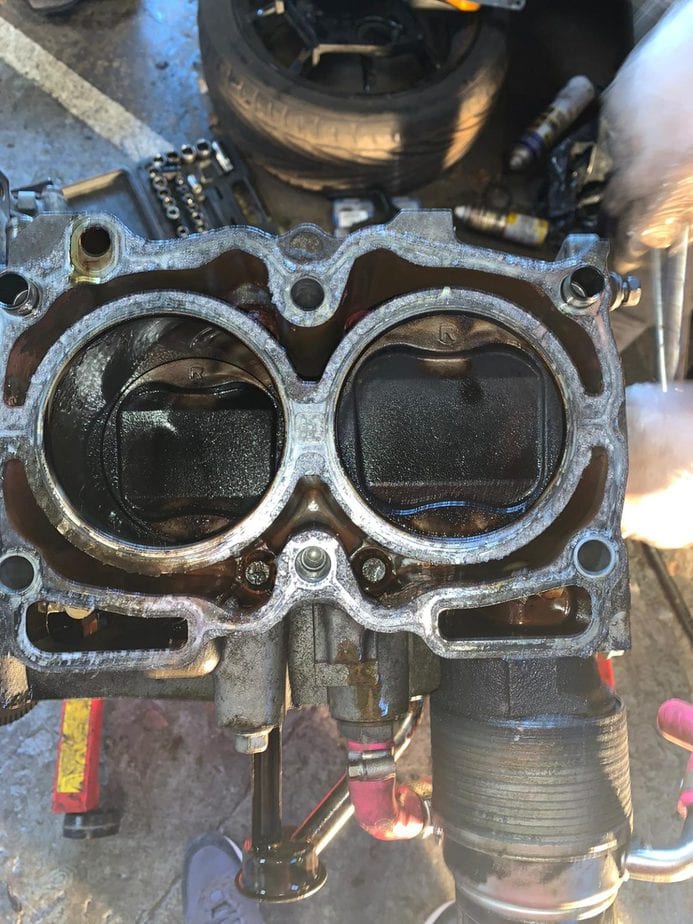

Pulling the heads, there was evidence of detonation on the pistons. Scoring in one of the cylinder bores, and horrible deposits all over the pistons and valves told me that the engine was definitely in dire need of attention. Lacking the time, I advised Danny to take the engine to a local machine shop, and get the bores honed, some oversize pistons fitted, valve seats cut, stem seals replaced and to get the rods, crankshaft and bearings inspected. It was a good job he did, because one of the rods turned out to be bent too! We got the engine back from the machine shop and fitted it to the car, along with a freshly powder coated intake manifold, a fresh engine wiring harness that I handmade (and had to get a couple of sensor plugs from a Subaru Legacy in a scrap yard!), and plenty of swearing. Having timed the process, it took about an hour and a half for us to get the engine in the car and all of the components plugged in to a point where we could start it.

I disarmed the immobiliser and turned the key. The car started on three cylinders, then cut out. Strange, I thought. The car was happy to run on three cylinders but then suddenly didn’t sound great. The reason it was running on three cylinders was due to an unplugged coil, so we remedied that and tried again.

Oddly enough, the car spluttered and barely ran on one cylinder to my surprise – and sounded like it completely lost compression. It was stupidly easy to turn by hand. The starter barely needed any effort to rotate it. Weirdly enough, it made no metallic grinding noises or anything when it spluttered. Keep this in mind.

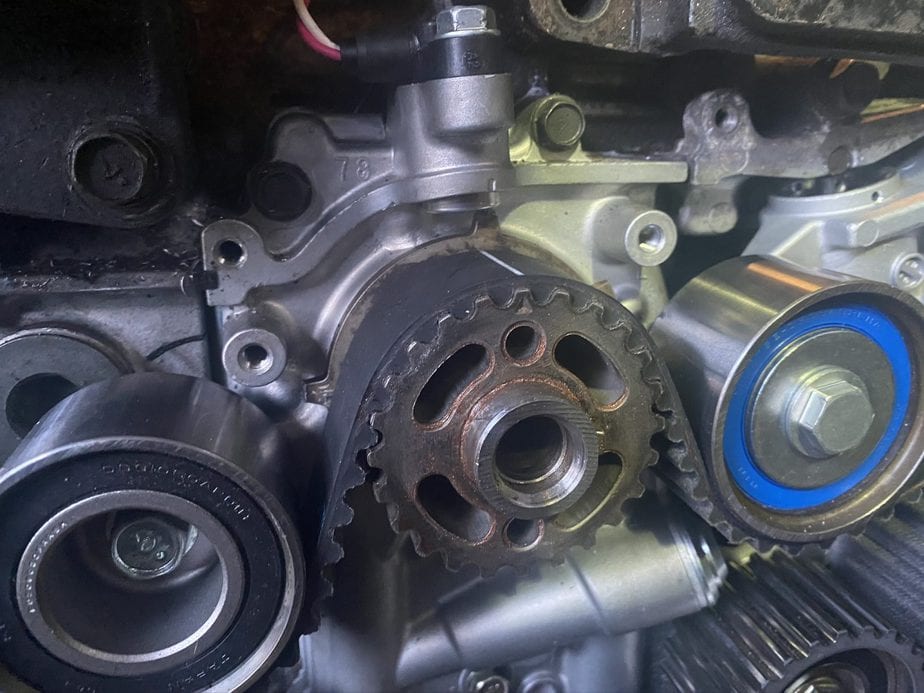

I decided to check the timing. I thought it didn’t sound like it bent the valves, but Subarus have an interesting way of controlling spark. On a four cylinder engine, you typically have a couple of ways to determine which piston needs firing on a sequential firing engine. If you have just one sensor i.e. a camshaft position sensor or crankshaft position sensor, an ECU may fire two cylinders at once in an attempt to accelerate the engine, and then determine where the sensor is in phase with the engine’s timing. Subaru EJ20s use two sensors, a camshaft position sensor on one of the intake cams, and a crankshaft position sensor. If the timing belt hasn’t been installed correctly or it skips a couple of teeth, it’s possible for the crankshaft to come out of phase with the camshaft, and the ECU will stop sending a signals to the coils and fuel injectors – perhaps in an effort to prevent bending valves?

Sure enough, the timing was a few degrees out. It looked like the timing belt had been incorrectly installed. On the off chance the engine did bend a valve, I opted to ask the machine shop to come out and correct their mistake. At least if it did bend a valve, that would be their problem then, and not mine.

However, with the timing belt correctly installed, the engine still refused to build compression. With a tester, it showed I was getting between 40-70psi on each cylinder, compared with the 140-170psi I should have according to the Subaru service manual. Utterly bemused, me and George took the engine back out of the car, somehow shoehorned it in to the boot of Danny’s car, and plonked it on the bench at the machine shop.

Me and George helped the machinists disassemble the engine, to identify the cause of the problem. To our surprise, there was grit in the engine! We removed the gudgeon pins and subsequently the pistons, to see the rings were completely worn and the piston skirts had been scratched. The worn piston rings would explain why we had practically no compression. The only place where grit would’ve came from would’ve been the intake manifold which was sent to a specialist to get powder coated. We collectively concluded that they hadn’t sealed the manifold properly when they grit blasted it before powder coating. Fortunately all we had to do was completely disassemble the engine, throw every part in the part washer, and replace the piston rings and head gaskets. Pretty easy rebuild. Taking no chances, we replaced the oil filter and also fitted a magnetic sump plug, on the off chance we hadn’t cleaned all of the engine properly.

In short, yes, somehow the engine was rebuilt twice, within a fortnight. Whilst the engine was at the shop for another day or two, I decided to tackle the immobiliser wiring, which looked like it had been installed by Stevie Wonder himself. Danny wanted rid of it, but I said it was easier to just relocate it and preserve the existing installation – don’t whack the wasp nest with a big stick if you don’t have to – otherwise you’re just asking for a whole world of hurt.

I set about by temporarily colour coding all of the wires (which are black for security purposes) and cutting them, so I could relocate and secure the immobiliser, which was probably the quickest part of the process. Wire by wire, I removed the colour coding, ran the wire neatly inline with the existing wiring loom, and spliced them back together with solder and heatshrink. Finally, I taped all the wires up into the existing loom, and the result is a virtually undetectable immobiliser install, and most importantly completely out of sight now.

A Scotsman once told me that fortune favours the brave; despite Danny wanting to sell the car for the seventieth time during this project, we pressed on, significantly with more caution. George washed and air blasted the manifolds for a good 6 hours before we fitted them to the car, of which I used this time to reinstall the engine, tidy up the vacuum system and some more of the car’s electrics. The indicator relays had been relocated to behind the radio, which I’m assuming was the same reason as to why I had to relocate a new horn relay there too: moisture ingress. The source of the moisture had been fixed previously, but the carpets must’ve just held the moisture and just promoted the corrosion of the relays. Simple enough to fix though, less than half an hour of soldering some new plugs to adapt for a modern, off-the-shelf relay. Did I mention I had to wire the window heater switch back up as someone repurposed it for a flame igniter in the exhaust?

Another attempt at starting the engine was made. In my anticipation, I forgot to let the fuel pump prime, but the engine sounded like it was going to catch. I cycled the ignition again, then gave it the beans.

The legendary EJ20 fitted with a TD05 turbo roared into life, sounding as smooth as a 4 cylinder boxer engine could without a downpipe installed. I feathered the throttle while we bled the coolant, to try and keep the engine above idle since it needed to be ran in properly with a bit of boost.

Unfortunately that’s where our story ends for now. With Coronavirus lockdown measures preventing access to the workshop, the Subaru sits patiently, waiting for us to fit the body panels, MOT it and get 500 miles of run in on it, before we can send all 16psi of boost to the tarmac.

Leave a Reply